Code for the Recurrent Neural Network in the presentation "Tensorflow and deep learning - without a PhD, Part 2"

The presentation itself is available here:

This sample has now been updated for Tensorflow 1.1. Please make sure you redownload the checkpoint files if you use rnn_play.py.

> python3 rnn_train.py

The script rnn_train.py trains a language model on the complete works of William Shakespeare. You can also train on Tensorflow Python code. See comments in the file.

The file rnn_train_stateistuple.py implements the same model using the state_is_tuple=True option in tf.nn.rnn_cell.MultiRNNCell (default). Training is supposedly faster (by ~10%) but handling the state as a tuple is a bit more cumbersome.

> tensorboard --logdir=log

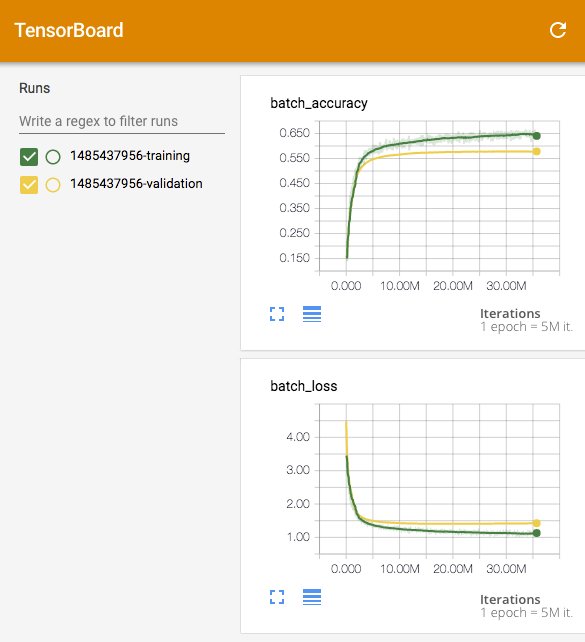

The training script rnn_train.py is set up to save training and validation data as "Tensorboard sumaries" in the "log" folder. They can be visualised with Tensorboard. In the screenshot below, you can see the RNN being trained on 6 epochs of Shakespeare. The training and valisation curves stay close together which means that overfitting is not a major issue here. You can try to add some dropout (pkeep=0.8 for example) but it will not improve the situation much becasue it is already quite good.

> python3 rnn_play.py

The script rnn_play.py uses a trained checkpoint to generate a new "Shakespeare" play.

You can also generate new "Tensorflow Python" code. See comments in the file.

Checkpoint files can be downloaded from here:

Fully trained on Shakespeare or Tensorflow Python source.

Partially trained to see how they make progress in training.

> python3 -m unittest tests.py

Unit tests can be run with the command above.

That is because you need to convert vectors of size CELLSIZE to size ALPHASIZE. The reduction of dimensions is best performed by a learned layer.

Why does it not work with just one cell? The RNN cell state should still enable state transitions, even without unrolling ?

Yes, a cell is a state machine and can represent state transitions like the fact that an there is a pending open parenthesis and that it will need to be closed at some point. The problem is to make the network learn those transitions. The learning algorithm only modifies weights and biases. The input state of the cell cannot be modified by it: that is a big problem if the wrong predictions returned by the cell are caused by a bad input state. The solution is to unroll the cell into a sequence of replicas. Now the learning algorithm can change the weights and biases to influence the state flowing from one cell in the sequence to the next (with the exception of the input state of the first cell)

3) OK, so this trained model will only be able to generate state transitions over a distance equal to the number of cells in an unrolled sequence, right ?

No, it will be able to learn state transitions over that distance only. However, when we will use the model to generate text, it will be able to produce correct state transitions over longer distances. For example, if the unrolling size is 30, the model will be able to correctly open and close parentheses over distances of 100 characters or more. But you will have to teach it this trick using examples of 30 or less characters.

4) So, now that I have unrolled the RNN cell, state passing is taken care of. I just have to call my train_step in a loop right ?

Not quite, you still need to save the last state of the unrolled sequence of cells, and feed it as the input state for the next minibatch in the traing loop.

All the character sequences in the first batch, must continue in the second batch and so on, because all the output states produced by the sequences in the first batch will be used as input states for the sequences of the second batch. txt.rnn_minibatch_sequencer is a utility provided for this purpose. It even continues sequences from one epoch to the next (apart from one sequence in the last batch of the epoch: the one where the training text finishes. There is no way to continue that one.) So there is no need to reset the state between epochs. The training will see at most one incoherent state per epoch, which is negligible.

Dropout in RNN theory is described here: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1409.2329.pdf

and further developed here: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1512.05287.pdf

The first thing to understand is that dropout can be applied to either the inputs of the outputs of a dense layer and this does not make much difference. If you look at the weights matrix of a dense neural network layer (here) you realize that applying dropout to inputs is equivalent to dropping lines in the weights matrix whereas applyting dropout to outputs is equivalent to dropping columns in the weights matrix. You might use a different dropout ratio for one and the other if your columns are significantly larger than your lines but that is the only difference.

In RNNs it is customary to add dropout to inputs in all cell layers as well as the output of the last layer, which actually serves as the input dropout of the softmax layer so there is no need to add that explicitly.

The first article says that dropout should be applied to RNN inputs+output but not states. In this approach, a random dropout mask is recomputed at every step of the unrolled sequence. This approach is called "naive dropout" and it's the one implemented in this sample.

The second article says that dropout should be applied to RNN inputs+output as well as states, using the same dropout mask for all the steps of the unrolled sequence. This approach is called "variational dropout" and the primitives for implementing it have recently been added to Tensorflow.

In the Shakespeare example, dropout (pkeep=0.8) can fix a slight tendency for overfitting visible between 10 and 20 training epochs.

When saving and restoring the model, you must name your placeholders and name your nodes if you want to target them by name in the restored version (when you run a session.run([-nodes-], feed_dict={-placeholders-}) using the restored model.

If you want to go deeper in the math, the one piece you are missing is the explanation of retropropagation, i.e. the algorithm used to compute gradients across multiple layers of neurons. Google it! It's useful if you want to re-implement gradient descent on your own, or understand how it is done. And it's not that hard. If the explanations do not make sense to you, it's probably because the explanations are bad. Google more :-)

The second piece of math I would advise you to read on is the math behind "sampled softmax" in RNNs. You need to write down the softmax equations, the loss functions, derive it, and then try to devise cheap ways of approximating this gradient. This is an active area of research.

The third interesting piece of mathematics is to understand why LSTMs converge while RNNs built with basic RNN blocks do not.

Good mathematical hunting!

TITUS ANDRONICUS

ACT I

SCENE III An ante-chamber. The COUNT's palace.

[Enter CLEOMENES, with the Lord SAY]

Chamberlain

Let me see your worshing in my hands.

LUCETTA

I am a sign of me, and sorrow sounds it.

[Enter CAPULET and LADY MACBETH]

What manner of mine is mad, and soon arise?

JULIA

What shall by these things were a secret fool,

That still shall see me with the best and force?

Second Watchman

Ay, but we see them not at home: the strong and fair of thee,

The seasons are as safe as the time will be a soul,

That works out of this fearful sore of feather

To tell her with a storm of something storms

That have some men of man is now the subject.

What says the story, well say we have said to thee,

That shall she not, though that the way of hearts,

We have seen his service that we may be sad.

[Retains his house]

ADRIANA What says my lord the Duke of Burgons of Tyre?

DOMITIUS ENOBARBUS

But, sir, you shall have such a sweet air from the state,

There is not so much as you see the store,

As if the base should be so foul as you.

DOMITIUS ENOY

If I do now, if you were not to seek to say,

That you may be a soldier's father for the field.

[Exit]